Chapter 2 Working with Web Data and APIs

Cameron Neylon

In many social science problems we have to augment our primary data with external data sources. Often the external data are available on the web, either on web pages directly or accessible through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). Gathering this data requires understanding how to scrape web pages or calling the APIs with parameters about the information we need. One common example of this is augmenting our primary data with data from the American Community Survey (ACS) or from Open Data Portals maintained by local, state, and federal agencies. These data sources can either be downloaded in bulk or used dynamically through APIs. Same is true for data from social media sources, such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. In this chapter we will cover tools (specifically using Python) that can be used by social science researchers to programmatically gather this type of external data from web pages and APIs.

2.1 Introduction

The Internet is an excellent resource for vast amounts of data on businesses, people, and their activity on social media. But how can we capture the information and make use of it as we might make use of more traditional data sources?

In social science, we often explore information on people, organizations, or locations. The web can be a rich source of additional information when doing this type of analysis, pointing to new sources of information, allowing a pivot from one perspective to another, or from one kind of query to another. Sometimes this data from the web is completely unstructured, existing in web pages spread across a site, and sometimes they are provided in a machine-readable form. In order to deal with this variety, we need a sufficiently diverse toolkit to bring all of this information together.8

Using the example of data on researchers and research outputs, we will focus this chapter on obtaining information directly from web pages (web scraping) as well as explore the uses of APIs—web services that allow programmatic retrieval of data. Both in this chapter and the next, you will see how the crucial pieces of integration often lie in making connections between disparate data sets and how in turn making those connections requires careful quality control. The emphasis throughout this chapter is on the importance of focusing on the purpose for which the data will be used as a guide for data collection. While much of this is specific to data about research and researchers, the ideas are generalizable to wider issues of data and public policy. While we use Python as the programming language in this chapter, data collection through web scraping and APIs can be done in most modern programming languages as well as using software that’s designed specifically for this purpose.

Box: Web Data and API Applications

In addition to the worked examples in this chapter here are a few other papers that show the wide variety of projects using data from web pages or APIs.9

Kim et al. (2016) use social media data about e-cigarettes from Twitter for public health research.

Goebel and Munzert (2018) used the online encyclopedia Wikipedia, to study how politicians enhance and change their appearance overtime. They trace changes to biographies coming from the parliament using data that cover the entire edit histories for biographies on all German members of parliament for the three last legislative periods. The authors have workshop material and code on GitHub how they performed the webscraping and API use for this project (https://github.com/simonmunzert/political-wikipedia-workshop).

King et al. (2013) investigate how censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression using a system to locate, download, and analyze the content of millions of social media posts originating from nearly 1,400 different social media services all over China before the Chinese government is able to find, evaluate, and censor (i.e., remove from the Internet) the subset they deem objectionable.

2.2 Scraping information from the web

With the range of information available on the web, our first task is to learn how to access it. The simplest approach is often to manually go to the web and look for data files or other information. For instance, on the NSF website10 it is possible to obtain data downloads of all grant information. Sometimes data are available through web pages or we only want a subset of this information. In this case web scraping is often a viable approach.

Web scraping involves writing code to download and process web pages programmatically. We need to look at the website, identify how to get the information we want from it, and then write code to do it. Many websites deliberately make this difficult to prevent easy access to their underlying data while some websites explicitly prohibit this type of activity in their terms of use. Another challenge when scraping data from websites is that the structure of the websites changes often, requiring researchers to keep updating their code. This is also important to note when using the code in this chapter. While the code accurately captures the data from the website at the time of this writing, it may not be valid in the future as the structure and content of the website changes.

2.2.1 Obtaining data from websites

Let us suppose we are interested in obtaining information on those investigators that are funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). HHMI has a website that includes a search function for funded researchers, including the ability to filter by field, state, and role. But there does not appear to be a downloadable data set of this information. However, we can automate the process with code to create a data set that you might compare with other data.

Getting information from this web page programmatically requires us to follow the following steps: 1. Constructing a URL that will give us the results we want 2. Getting the contents of the page using that URL 3. Processing the html response to extract the pieces of information we are looking for (such as names and specialties of the scientists)

** Constructing the URL **

This process involves first understanding how to construct a URL that will do the search we want. This is most easily done by playing with search functionality and investigating the URL structures that are returned.

With HHMI, if we do a general search and play with the structure of the URL, we can see some of the elements of the URL that we can think of as a query. As we want to see all investigators, we do not need to limit the search, and so with some fiddling we come up with a URL like the following. (We have broken the one-line URL into three lines for ease of presentation.)

http://www.hhmi.org/scientists/browse?kw=&sort_by=field_scientist_last_name&sort_order=ASC&items_per_page=24&page=0

We can click on different links on the page modify part of this URL to see how the search results change. For example, if we click on Sort by Institution, the URL changes to

If we click on next at the bottom, the url changes to https://www.hhmi.org/scientists/browse?sort_by=field_scientist_academic_institu&sort_order=ASC&items_per_page=24&page=1

This allows us to see that the URL is constructed using a few parameters, such as sort_by, sort_order, items_per_page, and page that can be programmatically modified to give us the search results that we want.

Getting the contents of the page from the URL

The requests module, available natively in Jupyter Python notebooks, is a useful set of tools for handling interactions with websites. It lets us construct the request that we just presented in terms of a base URL and query terms, as follows:

>> BASE_URL = "http://www.hhmi.org/scientists/browse"

>> query = {

"kw" : "",

"sort_by" : "field_scientist_last_name",

"sort_order" : "ASC",

"items_per_page" : 24,

"page" : None

}With our request constructed we can then make the call to the web page to get a response.

>> import requests

>> response = requests.get(BASE_URL, params=query)The first thing to do when building a script that hits a web page is to make sure that your call was successful. This can be checked by looking at the response code that the web server sent—and, obviously, by checking the actual HTML that was returned. A 200 code means success and that everything should be OK. Other codes may mean that the URL was constructed wrongly or that there was a server error.

>> response.status_code

200Processing the html response

With the page successfully returned, we now need to process the text it contains into the data we want. This is not a trivial exercise. Web pages are typically written in a “markup” language called Hyptertext Markup Language (HTML). This language tells the web browser how to display the content on that web page such as making a piece of text bold or in italics, creating numbered lists, or showing images. When we use Python to retrieve a webpage, running the code gives us the HTML text. We then have to process this text to extract the content that we care about. There are a range of tools in Python that can help with processing HTML data. One of the most popular is a module BeautifulSoup (Richardson n.d.), which provides a number of useful functions for this kind of processing. The module documentation provides more details.

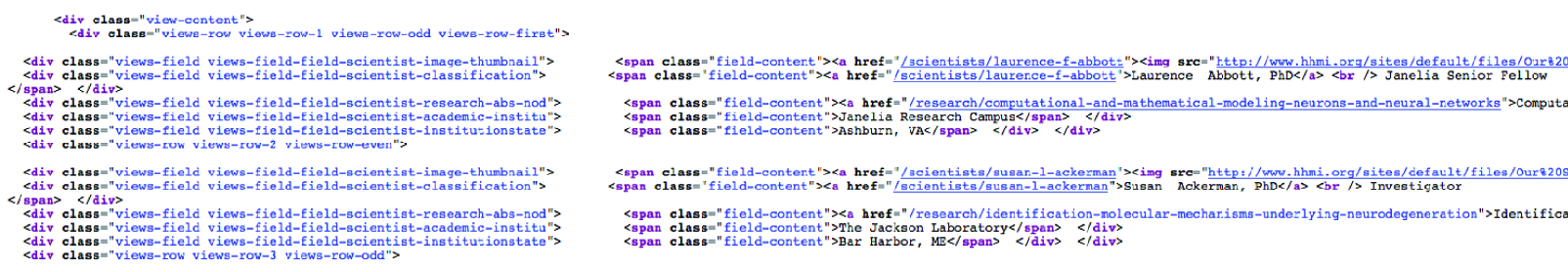

We need to check the details of the page source to find where the information we are looking for is kept (see, for example, Figure 2.1). Here, all the details on HHMI investigators can be found in a <div> element with the class attribute view-content. This structure is not something that can be determined in advance. It requires knowledge of the structure of the page itself. Nested inside this <div> element are another series of divs, each of which corresponds to one investigator. These have the class attribute view-rows. Again, there is nothing obvious about finding these, it requires a close examination of the page HTML itself for any specific case you happen to be looking at.

Figure 2.1: Source HTML from the portion of an HHMI results page containing information on HHMI investigators; note that the webscraping results in badly formatted html which is difficult to read.

We first process the page using the BeautifulSoup module (into the variable soup) and then find the div element that holds the information on investigators (investigator_list). As this element is unique on the page (I checked using my web browser), we can use the find method. We then process that div (using find_all) to create an iterator object that contains each of the page segments detailing a single investigator (investigators).

>> from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

>> soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html5lib")

>> investigator_list = soup.find('div', class_ = "view-content")

>> investigators = investigator_list.find_all("div", class_ = "views-row")As we specified in our query parameters that we wanted 24 results per page, we should check whether our list of page sections has the right length.

>> len(investigators)

20# Given a request response object, parse for HHMI investigators

def scrape(page_response):

# Obtain response HTML and the correct <div> from the page

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html5lib")

inv_list = soup.find('div', class_ = "view-content")

# Create a list of all the investigators on the page

investigators = inv_list.find_all("div", class_ = "views-row")

data = [] # Make the data object to store scraping results

# Scrape needed elements from investigator list

for investigator in investigators:

inv = {} # Create a dictionary to store results

# Name and role are in same HTML element; this code

# separates them into two data elements

name_role_tag = investigator.find("div",

class_ = "views-field-field-scientist-classification")

strings = name_role_tag.stripped_strings

for string,a in zip(strings, ["name", "role"]):

inv[a] = string

# Extract other elements from text of specific divs or from

# class attributes of tags in the page (e.g., URLs)

research_tag = investigator.find("div",

class_ = "views-field-field-scientist-research-abs-nod")

inv["research"] = research_tag.text.lstrip()

inv["research_url"] = "http://hhmi.org"

+ research_tag.find("a").get("href")

institution_tag = investigator.find("div",

class_ = "views-field-field-scientist-academic-institu")

inv["institute"] = institution_tag.text.lstrip()

town_state_tag = investigator.find("div",

class_ = "views-field-field-scientist-institutionstate")

inv["town"], inv["state"] = town_state_tag.text.split(",")

inv["town"] = inv.get("town").lstrip()

inv["state"] = inv.get("state").lstrip()

thumbnail_tag = investigator.find("div",

class_ = "views-field-field-scientist-image-thumbnail")

inv["thumbnail_url"] = thumbnail_tag.find("img")["src"]

inv["url"] = "http://hhmi.org"

+ thumbnail_tag.find("a").get("href")

# Add the new data to the list

data.append(inv)

return dataFinally, we need to process each of these segments to obtain the data we are looking for. This is the actual “scraping” of the page to get the information we want. Again, this involves looking closely at the HTML itself, identifying where the information is held, what tags can be used to find it, and often doing some post-processing to clean it up (removing spaces, splitting different elements up, etc.).

Listing Investigators provides a function to handle all of this. The function accepts the response object from the requests module as its input, processes the page text to soup, and then finds the investigator_list as above and processes it into an actual list of the investigators. For each investigator it then processes the HTML to find and clean up the information required, converting it to a dictionary and adding it to our growing list of data.

Let us check what the first two elements of our data set now look like. You can see two dictionaries, one relating to Laurence Abbott, who is a senior fellow at the HHMI Janelia Farm Campus, and one for Susan Ackerman, an HHMI investigator based at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. Note that we have also obtained URLs that give more details on the researcher and their research program (research_url and url keys in the dictionary) that could provide a useful input to textual analysis or topic modeling (see Chapter Text Analysis).

>> data = scrape(response)

>> data[0:2]

[{'institute': u'Janelia Research Campus ',

'name': u'Laurence Abbott, PhD',

'research': u'Computational and Mathematical Modeling of Neurons and Neural... ',

'research_url': u'http://hhmi.org/research/computational-and-mathematical-modeling-neurons-and-neural-networks',

'role': u'Janelia Senior Fellow',

'state': u'VA ',

'thumbnail_url': u'http://www.hhmi.org/sites/default/files/Our%20Scientists/Janelia/Abbott-112x112.jpg',

'town': u'Ashburn',

'url': u'http://hhmi.org/scientists/laurence-f-abbott'},

{'institute': u'The Jackson Laboratory ',

'name': u'Susan Ackerman, PhD',

'research': u'Identification of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying... ',

'research_url': u'http://hhmi.org/research/identification-molecular-mechanisms-underlying-neurodegeneration',

'role': u'Investigator',

'state': u'ME ',

'thumbnail_url':

u'http://www.hhmi.org/sites/default/files/Our%20Scientists/Investigators/Ackerman-112x112.jpg',

'town': u'Bar Harbor',

'url': u'http://hhmi.org/scientists/susan-l-ackerman'}]** Programmatically Iterating over the Search Results **

Now we know we can process a page from a website to generate useful structured data. However, this was only the first page of results. We need to do this for each page of results if we want to capture all the HHMI investigators. We could just look at the number of pages that our search returned manually, but to make this more general we can actually scrape the page to find that piece of information and use that to calculate how many pages we need to iterate through.

The number of results is found in a div with the class “view-headers” as a piece of free text (“Showing 1–20 of 493 results”). We need to grab the text, split it up (we do so based on spaces), find the right number (the one that is before the word “results”) and convert that to an integer. Then we can divide by the number of items we requested per page (20 in our case) to find how many pages we need to work through. A quick mental calculation confirms that if page 0 had results 1–20, page 24 would give results 481–493.

>> # Check total number of investigators returned

>> view_header = soup.find("div", class_ = "view-header")

>> words = view_header.text.split(" ")

>> count_index = words.index("results.") - 1

>> count = int(words[count_index])

>> # Calculate number of pages, given count & items_per_page

>> num_pages = count/query.get("items_per_page")

>> num_pages

24Then it is a matter of putting the function we constructed earlier into a loop to work through the correct number of pages. As we start to hit the website repeatedly, we need to consider whether we are being polite. Most websites have a file in the root directory called robots.txt that contains guidance on using programs to interact with the website. In the case of http://hhmi.org the file states first that we are allowed (or, more properly, not forbidden) to query http://www.hhmi.org/scientists/ programmatically. Thus, you can pull down all of the more detailed biographical or research information, if you so desire. The file also states that there is a requested “Crawl-delay” of 10. This means that if you are making repeated queries (as we will be in getting the 24 pages), you should wait for 10 seconds between each query. This request is easily accommodated by adding a timed delay between each page request.

>> for page_num in range(num_pages):

>> # We already have page zero and we need to go to 24:

>> # range(24) is [0,1,...,23]

>> query["items_per_page"] = page_num + 1

>> page = requests.get(BASE_URL, params=query)

>> # We use extend to add list for each page to existing list

>> data.extend(scrape(page))

>> print("Retrieved and scraped page number:", query.get("items_per_page"))

>> time.sleep(10) # robots.txt at hhmi.org specifies a crawl delay of 10 seconds

Retrieved and scraped page number: 1

Retrieved and scraped page number: 2

...

Retrieved and scraped page number: 24Finally we can check that we have the right number of results after our scraping. This should correspond to the 493 records that the website reports.

>> len(data)

4932.2.2 Limits of scraping

While scraping websites is often necessary, is can be a fragile and messy way of working. It is problematic for a number of reasons: for example, many websites are designed in ways that make scraping difficult or impossible, and other sites explicitly prohibit this kind of scripted analysis. (Both reasons apply in the case of the NSF and Grants.gov websites, which is why we use the HHMI website in our example.) The structure of websites also changes frequently, forcing you to continuously modify your code to keep up with the structure.

In many cases a better choice is to process a data download from an organization. For example, the NSF and Wellcome Trust both provide data sets for each year that include structured data on all their awarded grants. In practice, integrating data is a continual challenge of figuring out what is the easiest way to proceed, what is allowed, and what is practical and useful. The selection of data will often be driven by pragmatic rather than theoretical concerns.

Increasingly, organizations are providing APIs to enable scripted and programmatic access to the data they hold. These tools are much easier and generally more effective to work with. They are the focus of much of the rest of this chapter.

2.3 Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)

An API is simply a tool that allows a program to interface with a service. APIs can take many different forms and be of varying quality and usefulness. In this section we will focus on one common type of API and examples of important publicly available APIs relevant to research communications. We will also cover combining APIs and the benefits and challenges of bringing multiple data sources together.

2.3.1 Relevant APIs and resources

There is a wide range of other sources of information that can be used in combination with the APIs featured above to develop an overview of research outputs and of where and how they are being used. There are also other tools that can allow deeper analysis of the outputs themselves. Table 2.1 gives a partial list of key data sources and APIs that are relevant to the analysis of research outputs.

| Source | Description | API | Free |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bibliographic Data | |||

| PubMed | An online index that combines bibliographic data from Medline and PubMed Central. PubMed Central and Europe PubMed Central also provide information. | Y | Y |

| Web of Science | The bibliographic database provided by Thomson Reuters. The ISI Citation Index is also available. | Y | N |

| Scopus | The bibliographic database provided by Elsevier. It also provides citation information. | Y | N |

| Crossref | Provides a range of bibliographic metadata and information obtained from members registering DOIs. | Y | Y |

| Google Scholar | Provides a search index for scholarly objects and aggregates citation information. | N | Y |

| Microsoft Academic Search | Provides a search index for scholarly objects and aggregates citation information. Not as complete as Google Scholar, but has an API. | Y | Y |

| Social Media | |||

| Altmetric.com | A provider of aggregated data on social media and mainstream media attention of research outputs. Most comprehensive source of information across different social media and mainstream media conversations. | Y | N |

| Provides an API that allows a user to search for recent tweets and obtain some information on specific accounts. | Y | Y | |

| The Facebook API gives information on the number of pages, likes, and posts associated with specific web pages | Y | Y | |

| Author Profiles | |||

| ORCID | Unique identifiers for research authors. Profiles include information on publication lists, grants, and affiliations. | Y | Y |

| CV-based profiles, projects, and publications. | Y | * | |

| Funder Information | |||

| Gateway to Research | A database of funding decisions and related outputs from Research Councils UK. | Y | Y |

| NIH Reporter | Online search for information on National Institutes of Health grants. Does not provide an API but a downloadable data set is available. | N | Y |

| NSF Award Search | Online search for information on NSF grants. Does not provide an API but downloadable data sets by year are available. | N | Y |

*The data are restricted: sometimes fee based, other times not.

2.3.2 RESTful APIs, returned data, and Python wrappers

The APIs we will focus on here are all examples of RESTful services. REST stands for Representational State Transfer (Wikipedia n.d.; Fielding and Taylor 2002), but for our purposes it is most easily understood as a means of transferring data using web protocols. Other forms of API require additional tools or systems to work with, but RESTful APIs work directly over the web. This has the advantage that a human user can also with relative ease play with the API to understand how it works. Indeed, some websites work simply by formatting the results ofAPI calls.

As an example let us look at the Crossref API. This provides a range of information associated with Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) registered with Crossref. DOIs uniquely identify an object, and Crossref DOIs refer to research objects, primarily (but not entirely) research articles. If you use a web browser to navigate to http://api.crossref.org/works/10.1093/nar/gni170, you should receive back a webpage that looks something like the following. (We have laid it out nicely to make it more readable.)

{ "status" : "ok",

"message-type" : "work",

"message-version" : "1.0.0",

"message" :

{ "subtitle": [],

"subject" : ["Genetics"],

"issued" : { "date-parts" : [[2005,10,24]] },

"score" : 1.0,

"prefix" : "http://id.crossref.org/prefix/10.1093",

"author" : [ "affiliation" : [],

"family" : "Whiteford",

"given" : "N."}],

"container-title" : ["Nucleic Acids Research"],

"reference-count" : 0,

"page" : "e171-e171",

"deposited" : {"date-parts" : [[2013,8,8]],

"timestamp" : 1375920000000},

"issue" : "19",

"title" :

["An analysis of the feasibility of short read sequencing"],

"type" : "journal-article",

"DOI" : "10.1093/nar/gni170",

"ISSN" : ["0305-1048","1362-4962"],

"URL" : "http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gni170",

"source" : "Crossref",

"publisher" : "Oxford University Press (OUP)",

"indexed" : {"date-parts" : [[2015,6,8]],

"timestamp" : 1433777291246},

"volume" : "33",

"member" : "http://id.crossref.org/member/286"

}

}This is a package of JavaScript Object Notation (JSON)11 data returned in response to a query. The query is contained entirely in the URL, which can be broken up into pieces: the root URL (http://api.crossref.org) and a data “query,” in this case made up of a “field” (works) and an identifier (the DOI 10.1093/nar/gni170). The Crossref API provides information about the article identified with this specific DOI.

2.4 Using an API

Similar to what we did with web scraping, using an API involves 1) constructing HTTP requests and 2) Processing the data that are returned. Here we use the Crossref API to illustrate how this is done. Crossref is the provider of DOIs used by many publishers to uniquely identify scholarly works. Crossref is not the only organization to provide DOIs. The scholarly communication space DataCite is another important provider. The documentation is available at the Crossref website.12

Once again the requests Python library provides a series of convenience functions that make it easier to make HTTP calls and to process returned JSON. Our first step is to import the module and set a base URL variable.

>> import requests

>> BASE_URL = "http://api.crossref.org/"A simple example is to obtain metadata for an article associated with a specific DOI. This is a straightforward call to the Crossref API, similar to what we saw earlier.

>> doi = "10.1093/nar/gni170"

>> query = "works/"

>> url = BASE_URL + query + doi

>> response = requests.get(url)

>> url

http://api.crossref.org/works/10.1093/nar/gni170

>> response.status_code

200The response object that the requests library has created has a range of useful information, including the URL called and the response code from the web server (in this case 200, which means everything is OK). We need the JSON body from the response object (which is currently text from the perspective of our script) converted to a Python dictionary. The requests module provides a convenient function for performing this conversion, as the following code shows. (All strings in the output are in Unicode, hence the u´ notation.)

>> response_dict = response.json()

>> response_dict

{ u'message' :

{ u'DOI' : u'10.1093/nar/gni170',

u'ISSN' : [ u'0305-1048', u'1362-4962' ],

u'URL' : u'http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gni170',

u'author' : [ {u'affiliation' : [],

u'family' : u'Whiteford',

u'given' : u'N.'} ],

u'container-title' : [ u'Nucleic Acids Research' ],

u'deposited' : { u'date-parts' : [[2013, 8, 8]],

u'timestamp' : 1375920000000 },

u'indexed' : { u'date-parts' : [[2015, 6, 8]],

u'timestamp' : 1433777291246 },

u'issue' : u'19',

u'issued' : { u'date-parts' : [[2005, 10, 24]] },

u'member' : u'http://id.crossref.org/member/286',

u'page' : u'e171-e171',

u'prefix' : u'http://id.crossref.org/prefix/10.1093',

u'publisher' : u'Oxford University Press (OUP)',

u'reference-count' : 0,

u'score' : 1.0,

u'source' : u'Crossref',

u'subject' : [u'Genetics'],

u'subtitle' : [],

u'title' : [u'An analysis of the feasibility of short read sequencing'],

u'type' : u'journal-article',

u'volume' : u'33'

},

u'message-type' : u'work',

u'message-version' : u'1.0.0',

u'status' : u'ok'

}This data object can now be processed in whatever way the user wishes, using standard manipulation techniques.

The Crossref API can, of course, do much more than simply look up article metadata. It is also valuable as a search resource and for cross-referencing information by journal, funder, publisher, and other criteria. More details can be found at the Crossref website.

2.5 Another example: Using the ORCID API via a wrapper

ORCID, which stands for “Open Research and Contributor Identifier” (see orcid.org; see also (Haak et al. 2012)), is a service that provides unique identifiers for researchers. Researchers can claim an ORCID profile and populate it with references to their research works, funding and affiliations. ORCID provides an API for interacting with this information. For many APIs there is a convenient Python wrapper that can be used. The ORCID–Python wrapper works with the ORCID v1.2 API to make various API calls straightforward. This wrapper only works with the public ORCID API and can therefore only access publicly available data.

Using the API and wrapper together provides a convenient means of getting this information. For instance, given an ORCID, it is straightforward to get profile information. Here we get a list of publications associated with my ORCID and look at the the first item on the list.

>> import orcid

>> cn = orcid.get("0000-0002-0068-716X")

>> cn

<Author Cameron Neylon, ORCID 0000-0002-0068-716X>

>> cn.publications[0]

<Publication "Principles for Open Scholarly Infrastructures-v1">The wrapper has created Python objects that make it easier to work with and manipulate the data. It is common to take the return from an API and create objects that behave as would be expected in Python. For instance, the publications object is a list populated with publications (which are also Python-like objects). Each publication in the list has its own attributes, which can then be examined individually. In this case the external IDs attribute is a list of further objects that include a DOI for the article and the ISSN of the journal the article was published in.

>> len(cn.publications)

70

>> cn.publications[12].external_ids

[<ExternalID DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001677>, <ExternalID ISSN:1545-7885>]As a simple example of data processing, we can iterate over the list of publications to identify those for which a DOI has been provided. In this case we can see that of the 70 publications listed in this ORCID profile (at the time of testing), 66 have DOIs.

>> exids = []

>> for pub in cn.publications:

if pub.external_ids:

exids = exids + pub.external_ids

>> DOIs = [exid.id for exid in exids if exid.type == "DOI"]

>> len(DOIs)

66Wrappers generally make operating with an API simpler and cleaner by abstracting away the details of making HTTP requests. Achieving the same by directly interacting with the ORCID API would require constructing the appropriate URLs and parsing the returned data into a usable form. Where a wrapper is available it is generally much easier to use. However, wrappers may not be actively developed and may lag the development of the API. Where possible, use a wrapper that is directly supported or recommended by the API provider.

2.6 Integrating data from multiple sources

We often must work across multiple data sources to gather the information needed to answer a research question. A common pattern is to search in one location to create a list of identifiers and then use those identifiers to query another API. In the ORCID example above, we created a list of DOIs from a single ORCID profile. We could use those DOIs to obtain further information from the Crossref API and other sources. This models a common path for analysis of research outputs: identifying a corpus and then seeking information on its performance.

One task we often want to do is to analyze relationships between people. As an exercise, we suggest writing code that is able to generate data about relationships between researchers working in similar areas. This could involve using data sources related to researchers, publications, citations and tweets about those publications, and researchers who are citing or tweeting about them. One way of generating this data for further analysis is to use APIs that give you different pieces of this information and connect them programmatically. We could take the following steps to do that:

Given a twitter handle, get the ORCID for that twitter handle. From the ORCID, get a list of DOIs. For each DOI, get citations, citing articles, tweets (and twitter handles) associated.

The result is a list of related twitter handles that can be analyzed to look for communities and networks.

The goal of this example is to use ORCID and Crossref to collect a set of identifiers and use a range of APIs to gather metadata and information the articles performance. The worked example is using the PLOS Lagotto API. Lagotto is the software that was built to support the Article Level Metrics program at PLOS, the open access publisher, and its API provides information on various metrics of PLOS articles. A range of other publishers and service providers, including Crossref, also provide an instance of this API, meaning the same tools can be used to collect information on articles from a range of sources.

2.7 Summary

This chapter focused on approaches to augment our data with external data sources on the Web. We provided steps and code to gather data web pages directly or through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). While scraping websites is often necessary, it can be fragile because 1) many websites are designed in ways that make scraping difficult or impossible (or explicitly prohibit it), and 2) the structure of websites also changes frequently, forcing you to continuously modify your code to match their structure. Increasingly, organizations are providing APIs to enable scripted and programmatic access to the data they hold. There are many good introductions to web scraping using BeautifulSoup and other libraries as well as API usage in general. In addition, the APIs notebook of Chapter Workbooks provides a practical introduction to some of these techniques.13 Given the pace at which APIs and Python libraries change, however, the best and most up to date source of information is likely to be a web search.

As we collect data through scraping and APIs, we then have to understand how to effectively integrate it with our primary data since we may not have access to unique and reliable identifiers. The next chapter Chapter Record Linkage deals with issues of data cleaning, disambiguation, and linking different types of data sources to perform further analysis and research.

References

Fielding, Roy T., and Richard N. Taylor. 2002. “Principled Design of the Modern Web Architecture.” ACM Transactions on Internet Technology 2 (2). ACM: 115–50.

Göbel, Sascha, and Simon Munzert. 2018. “Political Advertising on the Wikipedia Marketplace of Information.” Social Science Computer Review 36 (2): 157–75.

Haak, Laurel L., Martin Fenner, Laura Paglione, Ed Pentz, and Howard Ratner. 2012. “ORCID: A System to Uniquely Identify Researchers.” Learned Publishing 25 (4): 259–64.

Kim, Yoonsang, Jidong Huang, and Sherry Emery. 2016. “Garbage in, Garbage Out: Data Collection, Quality Assessment and Reporting Standards for Social Media Data Use in Health Research, Infodemiology and Digital Disease Detection.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18 (2).

King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts. 2013. “How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression.” American Political Science Review 107 (2): 1–18.

The chapter Privacy and Confidentiality will discuss ethical issues when dealing with and using “publically” available data for research and policy purposes.↩

If you have examples from your own research using the methods we describe in this chapter, please submit a link to the paper (and/or code) here: https://textbook.coleridgeinitiative.org/submitexamples↩

JSON is an open standard way of storing and exchanging data.↩